| [8]

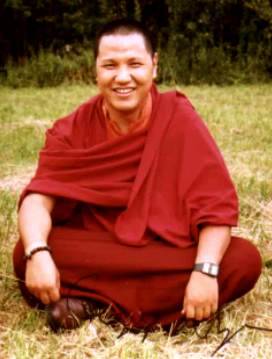

His Eminence the Tenth Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche

Karma Palden Rangjung Thrinle Kunkyab Gyaltsen Pal Sangpo

Six Preliminary Contemplations to Realize Relative Bodhicitta

as Taught by Pälden Atisha

&

An Introduction to “rGyal-srä-lag-len-sum-bcu-so-bdün –

The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva” by Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo

We consider ourselves practitioners of Mahayana, the Great Vehicle that presupposes having earnestly given rise to, heedfully upholding, and gladly increasing bodhicitta, the Sanskrit term for “a mind determined to awaken to enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings.” Without the sincere motivation, a disciple of Lord Buddha’s teachings is not a Mahayana practitioner. Therefore, before listening to these sublime instructions, I wish to ask you to recollect your motivation, to call to mind that you are receiving these teachings for the welfare of all sentient beings as well as for your own benefit, too. Why is it necessary to generate the pure motivation of bodhicitta before receiving these precious instructions?

As it is, living beings are subject to delusion, called ma-rig-pa in Tibetan, which means “non-recognition of intrinsic awareness.” Due to not recognizing the way things are and the way things arise and appear, living beings perpetuate the suffering and pain that samsaric existence inevitably entails. Misperception and misapprehension of appearances and experiences need to be overcome in order to put an end to the unsatisfactory experiences of conditioned existence, called samsara in Sanskrit. Nobody wants to suffer and experience pain. Every living being without exception wishes to be happy and free of suffering, but - lost for ways and means and therefore in an unremitting attempt to establish happiness and to avoid pain - unknowingly continue giving rise to frustration, agony, and suffering, sdug-bsnäl in Tibetan. Determined to overcome misery and woe, we need to know the right means to uproot its cause and its source, which is ma-rig-pa, “not knowing.” The only reliable way to uproot misperception and misapprehension is to arouse and generate the enlightened mind of bodhicitta, which is translated into Tibetan as byang-chub-kyi-sems.

There are two categories of bodhicitta: relative and absolute. Relative bodhicitta is experienced at two levels: the level of not clearly knowing how to overcome mistaken apprehension and the level of clearly knowing what needs to be done in order to definitely put an end to suffering and to reliably bring about lasting happiness and peace for oneself and for others. During the phase of misapprehension or delusion, a practitioner certainly has the wish to benefit others, yet he or she is still not aware of appropriate ways to help. He or she does realize that others suffer, recognizes the necessity to help, and arouses “bodhicitta of aspiration,” smön-pa’i-byang-chub-kyi-sems. When aware of how to give unfailing help and support to those in need, a practitioner is able to engage in reliable methods to truly benefit himself or herself as well as many others. This, then, is the practice called “bodhicitta of application,” ‘jug-pa’i-byang-chub-kyi-sems. So, relative bodhicitta has two aspects: bodhicitta of aspiration and bodhicitta of application.

Absolute bodhicitta means seeing emptiness of all phenomena - emptiness of an individual self and emptiness of all appearances, which does not imply a negation of appearances or an absence in phenomena of an ability to perform a function. Let us turn our attention to developing and increasing relative bodhicitta now.

Six Preliminary Contemplations to Realize Relative Bodhicitta

as Taught by Pälden Atisha

Pälden Atisha, the great Indian saint and sage, who lived approximately 982-1054 C.E., explained how to arouse and develop relative bodhicitta. He presented six preliminary steps that need to be contemplated successively in order to realize and integrate relative bodhicitta fully and effectively in our lives. The six contemplations are:

1) The first practice that Jowo rJe Atisha offered is to contemplate that in time that is without a beginning every living being, without exception and throughout the vast expanse of existence was once our kind and dear mother.

2) The second practice that excellent Atisha taught is again and again acknowledging and appreciating the fact that all living beings, who were once our dear mother, cared for us generously and with utmost concern.

3) The third practice is the realization of a Mahayana practitioner who understands that it is time to repay all living beings, our mothers, for having sacrificed so much in the past in order to help us. This may seem difficult for those persons who are in discord with their present mother to acknowledge and appreciate. Yet, such an attitude should not stop a Mahayana disciple from imagining uncountable lifetimes in which he or she experienced only goodness and worth because of the kindness of others. Therefore, the third contemplation is carried out so that a practitioner is encouraged and determined to turn his or her mind towards benefiting others.

4) The fourth practice that leads to realization of relative bodhicitta is generating and increasing loving kindness by contemplating the first line of “The Bodhicitta Prayer” we recited together: Sems-chen-tham-ched-bde-wa-dang-bde-wai-rgyu-dang-lden-par-gyur-chig - “May all living beings have happiness and its causes.”

5) The fifth step is generating and increasing compassion by reflecting the second line of the same prayer: sDug-bsnäl-dang-sdug-snäl-kyi-rgyu-dan-bräl-war-gyur-chig – “May all living beings be free from suffering and its causes.”

6) Having come to sincerely acknowledge and appreciate the first five contemplations, Pälden Atisha taught that the sixth step a Mahayana practitioner takes is actually engaging in joyful endeavour by taking on responsibilities that are inspired and moved by compassion for others. A sincere Mahayana practitioner never expects anyone else to do good in his or her stead and never thinks that it is too early to work for the welfare of others.

While developing bodhicitta, two expectations need to be abandoned from the very start, firstly, hoping that others return any goodness one is able to extend to them. The second wish a sincere practitioner needs to abandon while engaging in virtuous activities is hoping to be reborn in a higher realm after death so as to experience great joy for a long period of time. Both expectations need to be abandoned at the very beginning of practice. Expecting something in return for any help one can give pertains to this life; hoping to be reborn in a heavenly realm for any virtuous deeds performed now pertains to the next life.

Excellent Atisha offered a seventh contemplation that is practiced on how to firmly establish relative bodhicitta in one’s mind in order to enter and sincerely tread the worthy path of a bodhisattva, instead of giving in to complacency. He stressed the importance of practicing the six points thoroughly so that they become part of this very life. For instance, after having practiced calm-abiding meditation (shi-gnäs in Tibetan, shamata in Sanskrit) someone can conclude, “I have given rise to bodhicitta, in fact, I am meditating loving kindness and compassion.” These are merely thoughts and point to wishful thinking. If one spends time earnestly contemplating the six steps that Pälden Atisha suggested and that practitioners of the Kadampa tradition fervently follow, then one will be able to develop and realize genuine bodhicitta. Let us look at the Sanskrit term bodhisattva, translated into Tibetan as byang-chub-sems-pa, to more fully appreciate the purpose of actually taking on responsibilities for one’s own benefit and for that of others by following the way of a bodhisattva and leading a meaningful life.

Bodhisattvas are those individuals who practice bodhicitta. There are two types of bodhisattvas: ordinary bodhisattvas and noble bodhisattvas. There are five paths a bodhisattva traverses before reaching the highest stage of perfection. These five paths are: 1) the path of accumulation, 2) the path of practice or unification, 3) the path of seeing, 4) the path of meditation, and 5) the path of no-more-learning; in Tibetan: tshogs-lam, sbyor-lam, mthong-lam, sgom-lam, and mi-slob-pa’i-lam. The first type of bodhisattva, the ordinary bodhisattva, is someone who practices and realizes either the first or both of the first two paths. The second type, the noble bodhisattva, is someone who has reached and practices the third path of seeing or who has reached and is practicing one of the last two of the five paths. Bodhisattvas who are on or have successfully accomplished the third path of seeing have realized dharmata, the Sanskrit term for “suchness,” chös-nyid in Tibetan. Dharmata refers to emptiness and means that the true nature of every phenomenon and experience always remains “as such.”

Noble bodhisattvas see the way things appear (interdependently) and the way all things truly are (empty of inherent existence). They are therefore called “noble,” arya in Sanskrit and ‘phag-pa in Tibetan. Having realized the third stage of seeing emptiness, noble bodhisattvas have accomplished the first of the ten saintly levels of realization. The difference between an ordinary and a noble bodhisattva is whether or not he or she has realized emptiness. Noble bodhisattvas have seen emptiness, shunyata in Sanskrit, stong-pa-nyid in Tibetan, and are therefore disciples of Mahayana. This was a short presentation of the two types of bodhisattvas.

It is important to study texts like The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva in order to understand a bodhisattva’s motivation and practices and in order to arouse the wish to emulate them seriously so as to directly see emptiness and thereby enable all values of worth - that are always and already present within - to gradually unfold

from within. Let us now turn our attention to the theme of this seminar, “The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva.”

An Introduction to “rGyal-sräs-lag-len-sum-bcu-so-bdün –

The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva” by Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo

The author of the text, The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva was the Tibetan scholar named Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo. The name Thogme is the Tibetan translation of the Indian name Asanga, but the Tibetan sage and saint Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo should not be mistaken to be Mahapandita Asanga who lived in the 4 th century C.E. Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo was born in Central Tibet and lived from approximately 1295-1369 C.E. (See the introduction to The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva by Ngülchu Thogma, translated by members of the Marpa Translation Committee, Modern Printing Press, Kathmandu,1994.)

The Title

The Tibetan title of the text we will study together is “rGyal-sräs-lag-len-sum-bcu-so-bdün.” rGyal-sräs-lag-len means “the practices of the Victorious One’s sons and daughters.” rGyal is the “Victorious One” - Lord Buddha. Sräs are his “sons and daughters”; they are great bodhisattvas. Lag means “hand,” len (spelled bläng) means “received by the hand” and “to put into practice,” so lag-len means “the practices” of a bodhisattva. Sum-bcu-so-bdün, “thirty-seven,” points to the fact that the text consists of 37 verses that clearly elucidate a bodhisattva’s view, meditation, and actions.

The Homage

Namo Lokesvaraya.

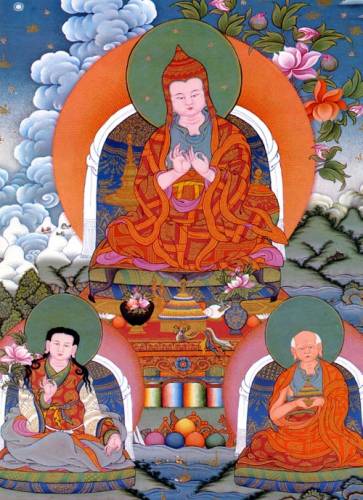

The text begins with a homage to the most noble object of refuge, Lokesvaraya in Sanskrit, who is Noble Chenrezig (spelled sbyan-räs-gzigs). “Namo Lokesvaraya” is the honorific way of commemorating the original language of the root text, the sacred language of India which was the homeland of Buddha Shakyamuni. Namo means “innermost homage.” Lokesvaraya was translated into Tibetan as 'Jig-rten-dbang-phyug and means “The Mighty Lord of the World.” He is the Lord of Love and Compassion, revered by Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo at the very beginning of the text. We, too, bow to ‘Phag-pa Chenrezig because he is a Buddha’s supreme protector. A supreme protector is recognized as being someone who perfectly embodies and manifests the immense love and compassion of all Buddhas of the three times (the past, present, and future).

‘Phag-pa Chenrezig reveals relative aspects and an absolute aspect. His relative aspects are the many depictions of him in various forms - with a white body and four arms, or with eleven heads and a thousand arms. There are paintings, statues, and photos that represent the relative aspects of most Noble Chenrezig. The absolute aspect, though, cannot be depicted since it transcends any thoughts or ideas that are formulated or imagined, while it is always and already present. Absolute Chenrezig is the true nature of our very own mind.

The essence of our mind is emptiness; the nature of our mind is clarity. The indivisibility of emptiness and clarity is the union of emptiness and loving kindness, the true nature of our mind. The absolute manifestation of Noble Chenrezig is mind’s true nature, sems-kyi-gnäs-lugs in Tibetan, “the way the mind abides.” Due to the overwhelming force of misperception and misapprehension, ma-rig-pa (“unawareness”, “not knowing”), ordinary living beings do not realize the true nature of their own mind, the true nature being the union of emptiness and loving kindness and compassion. Ordinary beings do not see and as a result feel separated from the absolute and pure manifestation of Noble Chenrezig. It is therefore necessary to contemplate and meditate representations of his relative aspects in the form of paintings, statues, and photos. The relative depictions and figures are contemplated and meditated as supports to gradually recognize and realize his absolute nature, which is, in truth, our very own mind.

The prayer “Namo Lokesvaraya” is least restricted to relative conditions that will always be mental constructs; it is the best verbal expression to honour the Lord of Love and Compassion. As long as the ultimate nature of one’s own mind has not been realized, it is fitting and very beneficial to pay homage to the relative aspects of his pure being, though.

Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo realized and experienced the virtuous qualities that Noble Chenrezig embodies and therefore he was empowered to write a second prayer of reverence. After having bowed to the Lord of Refuge with the honorific words “Namo Lokesvaraya,” he paid homage to the wonderful qualities of Chenrezig in detail and wrote:

Kan-gis-chös-kung-’gro-’ong-med-gzigs-kyang

‘gro-ba’i-dön-la-gchig-tu-brtsong-mzäd-pa’i

bla-ma-mchog-dang-sbyang-räs-gzigs-mgon-la

rtag-du-sgo-gsum-güs-päs-phyag-’tsäl-lo.

“To the One who sees that all phenomena neither come nor go

and who seeks only to benefit all beings,

to the supreme Lama and Protector Chenrezig

continually I pay homage in respect with body, speech, and mind.”

Translated by Michele Martin, in: The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva, page 7.

When paying homage to the supreme Lama and Protector Chenrezig, the two invaluable qualities that he embodies and manifests are addressed and honoured in the second prayer of veneration. These two qualities are vast knowledge and immeasurable love and compassion. Vast knowledge, mkhyen in Tibetan, is his first quality, which is perfect and unmistaken ascertainment of the way all things really are (empty of inherent self-existence) and the way all things arise and appear (dependent upon causes and conditions). mKhyen, “vast knowledge,” means perfect realization of emptiness. His second quality is called sning-rje in Tibetan. sNing-rje is unimpeded, uninterrupted, immense love and compassion for all sentient beings without exception. It is perfectly established through his immeasurable, non-dual, primordial awareness, yes-she in Tibetan. The union of vast knowledge and immeasurable love and compassion is the well-spring and root of Theg-pa-chen-po, the “Great Vehicle” of Buddhism, which is Mahayana.

What does the first line in the original text, “Kan-gis-chös-kung-’gro-’ong-med-gzigs-kyang – the One who sees that all phenomena neither come nor go” mean? Kan-gis is “the One” who possesses vast knowledge and immeasurable love and compassion and is Noble Chenrezig. Vast knowledge means that he sees that all phenomena (“phenomena” being the translation of the Sanskrit term dharma, which is chös in Tibetan) neither come nor go, that all phenomena are neither created nor cease, that no phenomenon is ever impeded, that no phenomenon is ever singular or multiple. Noble Chenrezig is the one who sees that nothing ever comes or goes, “’gro-’ong-med-pa-gzigs-pa,” the article pa meaning “the one.” He sees that nothing is ever created, nothing is impeded, nothing comes nor goes, nothing is singular nor multiple, and so forth. This is what he sees, gzigs the Tibetan term for “sees.” The object, which is his mind of vast knowledge and immense love and compassion, is vast because his mind is free of misapprehending creation and cessation, it is never impeded, it does not come nor go, and he does not give in to either samsara or to nirvana.

The term ‘ong-ba, “coming,” in the same line of the homage points to ordinary living beings like us, who are subject to ma-rig-pa, “delusion,” “unawareness.” Shes-rab, “discriminating awareness,” means recognizing that nothing arises and ceases, that nothing comes nor goes, that nothing is singular or multiple, i.e., no dharma has a truly existent self. Noble Chenrezig has realized shes-rab fully and therefore has perfect discriminating awareness that is free of dualistic perceptions and conceptions defined by erroneous beliefs in either one or a few of the eight ways of mistakenly clinging to dualistic extremes, which can never be based upon anything but erroneous suppositions. The eight erroneous suppositions that ordinary beings cling to are believing 1) that phenomena and experiences arise and cease of their own accord, 2) that phenomena and experiences come and go, 3) that phenomena and experiences consist of one or many parts or instants of time, and 4) that samsara and nirvana are distinct states. When shes-rab (the Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit term prajna) has been fully established in the mind of a noble practitioner, then he or she realizes emptiness and sees that there is no coming and no going. It is logical, too, that if there is no coming, then there is no going. It is also logical that if there is no creation, there is no cessation. The same realization applies to the other misapprehensions and is valid for all dharmas within samsara and nirvana.

The great Indian Mahapandita Nagarjuna, who founded the Madhyamaka Philosophical School around the first century C.E., realized and taught a precise mode of reasoning to refute the eight misapprehensions in order to prove shunyata, “emptiness,” which is the unconditional ground of everything that ever was, is, or will be. His major treatise, “Mahamadhyamakakarika,” remains to this day the root and source for any profound discourses carried out to analytically prove the truth of the middle-way, Madhyamaka in Sanskrit, rbU-ma in Tibetan, “middle” in this context meaning not bound by any limited assumptions that are mere superimpositions of what does not exist or a denial of what does appear and function. By realizing that nothing whatsoever within the vast expanse of being exists the way one thinks or supposes in the face of unawareness, then the eight ideas and suppositions are understood to be invalid and any attempt carried out to prove the self-existence of an entity or experience is automatically recognized as being futile.

Yet, in order to abandon clinging to dualistic assumptions it is not enough to just hear, read, or think about the profound analytical refutations and proofs that certify the middle between the extremes, the middle being freedom from limited suppositions that are always based upon conditions. It is not enough to intellectually understand and acknowledge all inadequate and unsatisfactory consequences that the eight postulations entail in order to overcome clinging to the way things do appear to a mind governed by ma-rig-pa, “unawareness.” These very deep instructions need to be experienced.

Out of limitless compassion and due to having realized that nothing springs forth haphazardly or coincidentally and simply vanishes later - that nothing comes and goes - ‘Phag-pa Chenrezig sees all living beings who are confused as to the way things are (empty of own existence and ever dependent upon causes and conditions) and who are bewildered as to the way things appear to be (as though existing free of causes and conditions). Therefore he has immense compassion for them. We, too, pay homage to ‘Phag-pa Chenrezig, who always abides in the state of non-dual, timeless awareness, who never moves away from profound wisdom that sees emptiness, and who never grows tired of manifesting the wonderful qualities of loving kindness and compassion for the benefit of everyone. The prayer of veneration that Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo offered with sincere faith, gratitude, and devotion is:

“To the One who sees that all phenomena neither come nor go

and who seeks only to benefit all beings,

to the supreme Lama and Protector Chenrezig

continually I pay homage in respect with body, speech, and mind.”

Most Excellent and Noble Chenrezig’s immense love and compassion are immeasurable. How can this be? He sees that all phenomena and experiences are devoid of inherent existence, i.e., devoid of a substantial self. He sees that all abstract and concrete things are empty of self-existence; he sees that all dharmas are emptiness. Seeing all phenomena, he has immense love and compassion. His direct realization of emptiness is his perfect view and is the cause of his immeasurable care and concern for others. In the absence of the perfect view, it is not possible to give rise to similar far-reaching qualities of being.

What is the perfect view? That nothing whatsoever possesses a concrete self, i.e., everything is empty of inherent existence and for that reason all phenomena and experiences are in a state of constant flux. But due to the force and power of unawareness, ma-rig-pa, one thinks there is a solid self, while in truth there isn’t. Due to not having realized emptiness or due to thinking that there is no emptiness, love and compassion remain delusive. If one realizes emptiness, then any activities carried out with loving kindness and compassion will be immense. If there were no absence of a self-existing entity, if all phenomena and experiences were not empty of own existence, if a self of an individual and phenomena (i.e., subject and objects) existed from their own side and forever (i.e., did not undergo change), then it would not be necessary to develop love and compassion since nothing could be changed. But there is no solid self of an entity that is a constant basis of imputation. There is not nothing either, so love and compassion are not in vain. Furthermore, if there were a truly existing self, in which case it would be fixed, static, and therefore permanent, then one would rightfully cling to it as that and would necessarily deny development, maturation, becoming. When the view that there is no solid, self-existing entity that is a constant, permanent existent is fully established, then clinging to a self will have been abandoned and great love and compassion will arise. Noble Chenrezig sees that all phenomena and experiences are devoid of own existence. He sees emptiness perfectly, the reason why Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo honoured his quality of vast knowledge and wrote: “(He) sees that all phenomena neither come nor go.”

Based upon realization of emptiness, immense love and compassion unfold. The wonderful activities of loving kindness and compassion that unfailingly benefit others are: generosity, ethics, patience, joyful endeavour, meditative concentration, and discriminating awareness or insight, which are known as “the six paramitas.” The six paramitas in Tibetan and Sanskrit are: 1) sbyin-pa (dana, “generosity”), 2) tsul-khrims (shila, “ethics”), 3) bzöd-pa (kshanti, “forebearance,” “patience”), 4) brtsong-’grüs (virya, “diligence,” “joyful endeavour”), 5) bsam-gtän (dyana, “meditative concentration”), and 6) shes-rab (prajna, “discriminating awareness,” “insight”). Paramita is a Sanskrit term and means “perfection.” It is translated into Tibetan as pha-rol-tu-phyin-pa, which literally means “reaching the other shore.” By practicing the six perfections, the endeavour of the mind that works for the welfare of others is vast and renders immeasurable benefits.

Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo addressed Noble Chenrezig as “the supreme Lama” when he offered innermost homage in the prayer that he composed. There are two types of Lamas, an ordinary Lama and a supreme Lama. There are many ordinary Lamas, but Noble Chenrezig is likened to a supreme Lama because he is a special Lama. He is a supreme protector because he has profound awareness as well as immense love and compassion. What does this mean? For us he is the supreme and special Lama because he embodies the wonderful qualities of the Mahayana view, Mahayana meditation practices, and Mahayana activities. This is the reason why Noble Chenrezig is supreme.

What does Lama mean? Many people think that a Lama can be identified by the colour of the robes he or she wears, or by his or her outer appearance, or by speaking while seated higher than others. The Lama revered in this prayer, though, refers to a highest teacher - a Mahayana teacher. The title “Lama” consists of two syllables. Lha means “highest,” ma is a negation, so Lama means “nobody is higher,” i.e., his qualities are unsurpassable. Who is the supreme Lama? Noble Chenrezig is the very embodiment of the unfailing love and compassion that all Buddhas have. He is inseparable from our very own Lama; he is one with our supreme Lama. He is also called “Protector” in the same line of the prayer because he only helps others. He protects living beings through his profound awareness and his ability to perform incalculable and invaluable activities. We, too, continuously pay homage and prostrate to the supreme Lama and Protector with deepest devotion and sincerest respect by means of our three doors, which are our body, speech, and mind.

The prayer states “at all times,” rtag-du in Tibetan. rTag-du means “continuously,” which is to say that we, too, venerate Noble Chenrezig from today until we attain enlightenment, i.e., Buddhahood. We can hardly imagine the highest aspect of his being, namely that he is actually always present in our mind, so we bow to Noble Chenrezig when he is depicted as having a white body, two faces, and four arms. We saw that his depictions represent his relative aspect, so honouring expressions of conditionality will not lead to ultimate fruition. In the introduction we saw that the essence of the mind is empty, that the nature of the mind is unimpeded clarity, furthermore that the indivisibility of emptiness and clarity is the union of awareness that realizes emptiness and loving kindness and compassion. We saw that the absolute manifestation of Noble Chenrezig is mind’s true nature, sems-kyi-gnäs-lug. When the true nature of one’s mind has been realized (i.e., when shes-rab, “discriminating awareness,” develops and ripens) then paying homage to the absolute aspect of most Noble Chenrezig is most beneficial.

What does it mean to pay homage with the three doors, sgo-gsum? A practitioner pays reverence with body, with speech, and with his or her innermost heart, which is the mind. First one arouses faith in Chenrezig. There are three kinds of faith and devotion, däd-pa in Tibetan: faith of belief (yid-ches-kyi-däd-pa), faith of aspiration (död-pa’i-däd-pa), and pure faith (dang-ba’i-däd-pa). Paying homage with the three doors of our body, speech, and mind is expressing deep veneration with one’s entire being.

The verse of homage above is a summary of the entire text and describes the source of ultimate realization, the source being faith and devotion. This verse pays innermost homage to the Lord of Refuge, the supreme Lama and Protector of all Buddhas - Noble Chenrezig. What are the practices of a bodhisattva? There are two levels of practice: receiving the precious teachings and meditating them diligently.

The Reason for Writing this Text

Gyatsäl Thogme Zangpo explained why he wrote the text in the next verse by describing the source and fruition of all Buddhas:

Phän-bde’i-’byung-gnäs-rzogs-pa’i-sangs-rgyäs-rnams

dam-chös-bsgrubs-läs-byung-ste-de-yang-ni

de-yi-lag-bläng-shes-la-rag-läs-päs

rgyäl-sräs-rnams-kyi-lag-bläng-bshäd-bar-bya.

“The perfect Buddhas, who are the source of benefit and bliss,

arise from having fully accomplished the genuine Dharma.

Since this depends upon knowing the practices,

I will explain the practices of bodhisattvas.”

Translated by Michele Martin, in: The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva, page 7.

The Tibetan original begins with a description of perfect Buddhas and tells us, “phän-bde’i-’byung-gnäs.” Phän means “true benefit,” and bde means “happiness” and “bliss,” so these qualities describe the complete realization of all perfect Buddhas, who are the source of everything good. ‘Byung is the Tibetan word for “arise.”

What is the source of all qualities of astounding goodness and worth? The perfect Buddhas, rzogs-pa’i-sangs-rgyäs, i.e., mind’s true nature. As long as the wonderful qualities of perfection have not unfolded from within, a practitioner has not realized Buddhahood. The immense qualities of a Buddha abide within all living beings without exception as ye-shes-rnying-po, “the innermost heart of primordial awareness-wisdom.” Simply listening to the instructions that say that when all negative dharmas (i.e., mistaken apprehensions and resulting harmful emotions) have been exhausted, then all wonderful qualities will be unleashed and Buddhahood will have been attained will not help anyone. Rather, it is necessary to engage in the practices of a bodhisattva in order to experience one’s true nature and to manifest all excellent qualities of goodness and worth that are always and already present within each and everyone.

If all qualities of innermost goodness and worth were not present in the ground of being as the basis, they could not arise as a result at fruition through practicing the path. All qualities are present within every living being as the basis. By releasing the beneficial results that manifest while progressing along the paths, then the basis and the root, which is Buddha within, will be established at fruition. If the basis of Buddhahood were not present, it could never emerge as a result. When all dharmas have been exhausted (i.e., overcome) and all beneficial qualities have arisen, then the innermost heart of enlightenment will appear clearly and fully. The magnificent qualities of Buddhas are great bliss and benefiting others, always. What does this mean? The line in the verse states that “The perfect Buddhas, who are the source of benefit and bliss, arise from having fully accomplished the genuine Dharma.”

How do the perfect Buddhas arise? As it is, there can never be a result without a cause. If there is no source for a perfect Buddha, then there is no result. The phase of an ordinary being is the basis, the cause. When a follower of the precious teachings practices and progresses along the paths, negative emotions and habits are slowly, slowly, slowly abandoned and invaluable qualities slowly, slowly, slowly arise and manifest. At fruition, genuine Dharma will have been thoroughly established with body, speech, and mind. As long as the magnificent result has not emerged, partial accomplishments are not what is meant by genuine Dharma.

Although all living beings are endowed with a Buddha’s most wonderful qualities, nevertheless, it is necessary to hear, contemplate, and meditate the invaluable instructions so that they manifest purely at fruition – thös-pa, bsam-pa, and bgom-pa meaning “to hear,” “to contemplate,” and “to meditate.” If one does not engage in these three trainings, then Buddhahood will remain a thing of naught and, even though all beneficial values of being abide within, they will not arise or appear.

Let us look at the five paths. They are divided into stage of learning and the stage of no-more -earning. The four first paths of learning are tshogs-lam, sbyor-lam, mthong-lam, and sgom-lam, i.e., the path of accumulation, the path of practice or unification, the path of seeing, and the path of meditation. While on the stage of learning, slob-pa’i-lam in Tibetan, a practitioner hears, contemplates, and meditates the precious teachings in order to realize and integrate the view fully in his or her life. The four paths of learning are the well-spring and source of genuine fruition, which is attained on the fifth path, which is the stage of no-more-learning, mi-slob-pa’i-lam (also called mthar-phyin-pa’i-lam, which means “the path of liberation”).

On the first path of tshogs-lam, “the path of accumulation,” a follower of Lord Buddha’s teachings arouses the mind of awakening, which is bodhicitta of aspiration. He or she then engages in the practices of the first five paramitas, “perfections,” until the sixth paramita has been accomplished, which is shes-rab, “awareness that transcends dualistic fixations concerning a subject and objects.” This is what is meant by seeing emptiness of all dharmas. By knowing and realizing what can be realized while practicing the four lower paths, knowledge and awareness of the true way that all dharmas are and appear is won. Finally, during the highest level of practice, while on the fifth path of no-more-learning, ye-shes will be perfected and the ultimate result attained, which is ye-shes-kyi-rzogs, “exalted, primordial awareness-wisdom.” When the two accumulations of merit and wisdom have been perfected, then the genuine Dharma will have arisen in the mind of a noble bodhisattva. If the two accumulations have not been perfected, then the genuine Dharma will not have been established. This is the meaning of the line in the homage: “Since this depends upon knowing the practices.”

There are two types of accumulation (tshogs-gnyis): accumulation of merit (bsöd-nams-kyi-tshogs) and accumulation of exalted awareness-wisdom (ye-shes-kyi-tshogs). What is the accumulation of merit? Gaining discriminating awareness, shes-rab. Practicing virtuous activities in the absence of discriminating awareness that sees emptiness is the accumulation of merit. What is the accumulation of wisdom? Engaging in virtuous activities for the welfare of others together with discriminating awareness is establishing ye-shes, “primordial awareness-wisdom.”

The termin shes-rab has many connotations. A few definitions are “intelligence,” “worldly knowledge,” “recognition,” “understanding interdependent origination.” Ye-shes, “primordial awareness-wisdom,” means realizing emptiness of what is called “the three circles,” ‘khor-gsum in Tibetan. Realization of the three circles means perfectly realizing 1) emptiness of a subject, 2) emptiness of objects, and 3) emptiness of actions. Having perfected ye-shes, a noble practitioner is fully aware of the fact that any merit accumulated is not only transitory but also empty. Primordial awareness-wisdom is realized when a practitioner upholds discriminating awareness while diligently proceeding along the paths, until he or she has realized emptiness of the three circles.

We saw that there are six paramitas, “perfections.” The first five perfections are generosity, ethics, patience, joyful endeavour, and meditative concentration. Practicing the first five perfections is accumulating merit. Realizing the sixth perfection, discriminating awareness, is what is meant by accumulating wisdom. Joyful endeavour, the fourth paramita, is practiced in order to unite the first three perfections with the fifth and sixth inseparably. Coming to realize the inseparability of merit that is accumulated by attaining perfection of discriminating awareness with body, speech, and mind is what is meant by accumulating wisdom.

Uniting the two accumulations of merit and wisdom engenders ye-shes, “non-dual, primordial awareness,“ which, in turn, gives rise to the emanation of three kayas, the Sanskrit term that was translated into Tibetan as sku-gsum, which means “three bodies of Buddhas.” By perfecting the accumulation of merit, two form bodies of a Buddha arise, the nirmanakya and the sambhogakaya. Kaya is the Sanskrit term translated into Tibetan as sku. The two form kayas are sprul-pa’i-sku and long-spyöd-rzogs-pa’i-sku and mean “emanation body” and “body of perfect enjoyment” – they benefit others immensely. By perfectly realizing a Buddha’s primordial awareness, the dharmakaya is attained. Dharmakaya is the Sanskrit term that is translated into Tibetan as chös-sku and means “the body of reality” or “truth body” – it benefits oneself most meaningfully.

In his treatise, entitled “Rigs-pa-drug-chu-pa - The Sixty Stanzas of Reasoning,” Mahapandita Nagarjuna wrote an aspiration prayer to attain the bodies of a Buddha through the accumulation of merit and the accumulation of wisdom. It is the dedication prayer that we recite at the end of any practice and reads:

dGe-ba-’di-yis-skye-bo-kung

bsöd-nams-ye-shes-tsogs-zogs-nae

bsöd-nams-ye-shes-läs-byung-ba

dam-pa-sku-gnis-thob-par-shog.

“May the virtue of accumulating supreme merit and wisdom-awareness

that arises from perfecting supreme merit and wisdom-awareness

be dedicated so that all living beings attain the two true bodies.”

Simply knowing how to attain Buddhahood will not be very helpful. Certainly, it is necessary to appreciate that the attainment of Buddhahood is possible, but it is crucial to practice with joyful endeavour, the fourth paramita, in order to accomplish fruition. Why is joyful endeavour so important? The practice of hearing, contemplating, and meditating the Buddhadharma with joyful endeavour expands the mind that has given rise to both types of bodhicitta, “a mind determined to awaken to enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings.” We saw that there is bodhicitta of aspiration and bodhicitta of application. When a bodhisattva sincerely engages in bodhicitta of application by practicing the paramitas with joyful endeavour, then he and she can easefully attain Buddhahood, which is fruition of the Great Vehicle, Mahayana. The Great Vehicle consists of learning and practicing 1) the path of the view, 2) the path of meditation, and 3) the path of actions. In the process, the mind expands and reaches out to help others with enthusiasm. Eventually, a noble bodhisattva will fully accomplish the accumulations of supreme merit and awareness-wisdom and at that point he and she will have achieved perfect Buddhahood.

This concludes the explanation of the introduction to The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva. Let us now spend a little time meditating bodhicitta together.

There are two types of meditation that can be practiced in order to realize genuine Dharma: analytical and experiential. Analytical meditation means contemplating the teachings, analysing what arises and appears to the mind, and meditating what has been understood with joyful endeavour. Experiential meditation means abiding in the true nature of the mind in order to actually experience the indivisibility of timeless awareness-wisdom and vast values of being. Everyone is free to meditate either the one or the other approach, but it is important to balance them and to practice both alternately.

Pälden Atisha taught that truly realizing and experiencing that the mind determined to achieve awakening is inseparably united with the mind of perfect awakening is the ultimate way of paying homage. Dhagpo Lha-je, rJe Gampopa, taught that practicing the three trainings of hearing, contemplating, and meditating is extremely beneficial and the best way to realize and manifest the pure and genuine Dharma.

Thank you very much.

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless (in number) as space (is vast in its extent).

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities, may I and all living beings without exception

swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

May virtue increase!

Venerable Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche presented the seminar in 2005, but only the first evening of the seminar is offered here. Translated from Tibetan & edited by Gaby Hollmann, Munich, 2005.

|