| [102]

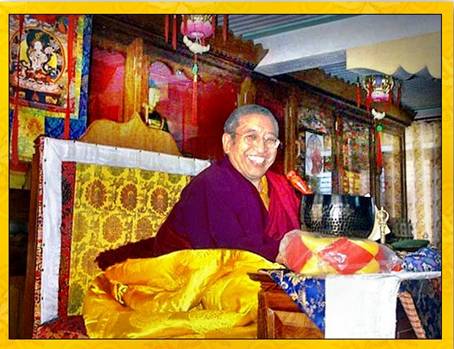

Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

Dharma & Dharmata – Part 2/4

Instructions on “Distinguishing Phenomena & Pure Being“

by Buddha Maitreya / composed by Asanga

presented at Thrangu Tashi Chöling in Boudhnath, Nepal, in 1992

3. Realising Dharmata

3.1. A Brief Explanation

3.2. An Extensive Explanation

3.2.1. Entering Dharmata in Six Points

3.2.2. Transformation in Ten Points (pts. 1 – 5)

* * *

3. Realising Dharmata

3.1. A Brief Explanation

The Root Text:

“If what appears as perceived does not exist, then what appears as perceiver does not exist. Due to this, there is also a rationale behind the breakthrough to freedom from all appearances of perceived and perceiver. Because without beginning, a volatile state prevails, duality’s not existing at all is what really exists.”

In the Buddha’s Sutras, many different kinds of emptinesses are mentioned. In the “Prajnaparamitasutra,” it is said that form, feeling, perception, etc., eye, ear, nose, tongue, and so forth are empty, i.e., that all internal and external phenomena lack inherent existence and therefore are emptiness. Apart from stating that they are empty of inherent existence, an explanation by way of deduction is not presented in Sutrayana. For this reason, it is difficult winning a definite understanding of the meaning of these statements through the Sutras. Therefore, to understand and gain certainty that phenomena are emptiness, many scholars and learned persons composed treatises and clearly elucidated the logic.

The main inferential reasoning on dependent arising was set forth by the Protector Nagarjuna. He explained in great detail that phenomena depend upon one another and appear by way of their dependence, in the light of which they are not truly established. To exemplify this relationship of dependence, I am holding two pieces of thread. We say that one piece is long and the other one is short. When I take a third thread, we see that the one that we thought was long is now short. The reason for this is that the thread we thought was long wasn’t long to begin with. In fact, concepts such as “long/short” are merely mental fabrications. This also applies to concepts such as “big/small, good/bad, beautiful/ugly, above/below, east/south/north/west” or anything that is fit to be an object of thought or knowledge.

Our world, which is called Jambudvipa in Sanskrit ('dzam-bu-gling in Tibetan), is often identified with the Indian subcontinent, but from the point of view of its human inhabitants, there is talk about “East and West.” Then, “East” is thought to be Asia and “West” is thought to be Europe and the Americas, but there is no reason for this other than that we have these concepts. Actually, the entire Earth is referred to as “Jambudvipa.” Some people might say, “That’s well and good when it comes to comparing qualities, but it has nothing to do with solid material existents, like a house, a building, a body.” Looking at a hand, for example, everyone sees it, but where is it? If we investigate, we will discover that the fingers, flesh, skin, and so on are not what we call “the hand.” Where, then, is the hand and how does that concept come about? We impute “hand” to the specific collection of parts that we see. This also applies to designations such as “right hand/left hand/legs/head” and all phenomena that we label and name. If we investigate, we will discover that every phenomenon is a collection of many different things and is merely imputed by our mind. That is why the Buddha taught that all things are empty of inherent existence, are emptiness. Does this mean that appearances do not exist? No. It means that designations are relative, e.g., an object is only seen as “long” in comparison to something that is seen as “short.” Likewise, even though there is no self, we think “I/me” in dependence upon what we consider “other” and vice versa. Applying this to mountains, we think that a mountain is near when we see that another mountain is far away.

Dharmata is not empty in the way that space is empty, rather, it is the suitability for phenomena to appear, and within emptiness, phenomena appear. This, then, is the putting together of conventional appearances and their ultimate lack of inherent establishment, which is not a contradiction. There is an unceasing appearance of both an inner apprehending mind and outer apprehended phenomena and therefore Maitreya taught and Asanga wrote in “Distinguishing Phenomena & Pure Being” about living beings’ strong latencies and dispositions. If we discuss this in terms of experiences, we can take the example of a dream. Due to latencies, various sorts of phenomena appear in a dream, but are they what they seem to be? No, they are not, nevertheless, they appear. This also illustrates the way in which conventional appearances dawn, despite being empty of independent existence.

We need to understand Dharmata (‘the nature of phenomena’) and until it becomes fully manifest, we need to meditate on it. Since the manner of abiding of Dharmata is perfect peace, as a result of practicing, our afflictions will diminish and will eventually cease. Then outer and inner interruptions that cause suffering will have been overcome. This is the reason it is really beneficial to realize the lack of establishment of external and internal appearances. There are the explanations of Dharmata by way of the path of the Sutra tradition and by way of the path of the Mantrayana-Vajrayana tradition. To abandon passion, aggression, mental fabrications, and so forth, which cause suffering, it is important to understand emptiness and realise that it is not nothing but has the quality of luminous clarity that is a factor of wisdom.

As discussed earlier, there are a variety of ways of indicating that external and internal phenomena are not inherently existent. There is the procedure of demonstrating that since external appearances are not established in the way that they seem, the consciousnesses that perceive and take them to be the way they are not are mistaken and therefore are also not established. There are the paths of inferential reasoning set forth by Madhyamikas, e.g., the reasoning of dependent origination, the reasoning that phenomena are not one or many, and so forth. In those ways, it is shown that external phenomena and internal minds are not inherently established, are not independent existents, rather, that their nature is emptiness. The school that propounds the view of emptiness is called “Rangtong” (Tibetan for ‘empty of self’). If we have gained certainty of Dharmata through the path of deduction and join the insight we have gained with meditation practice, our ascertainment of the nature of phenomena will become clearer and clearer, until we arrive at a direct perception of emptiness (shunyata in Sanskrit, stong-pa-nyid in Tibetan).

While it is true that all phenomena have the nature of emptiness, we should not misinterpret emptiness and think it is like a vacuum in which nothing exists, rather, it has radiant clarity that is the basis of a Buddha’s wisdom. Therefore it is taught that emptiness is endowed with the supreme of all aspects that is fit to appear and can be known. When perfectly realised, it is called “a Buddha’s wisdom.” For ordinary beings, it is the potency that is called sugatagarbaha in Sanskrit, de-dzhin-gshegs-pa’i-snying-po in Tibetan. It means ‘the essence of one who goes/has gone like that,’ i.e., like the Buddhas. The standard English translation of either the Sanskrit or Tibetan is “Buddha nature.” The teaching on the Buddha nature is referred to by scholars as the view of “Shentong” (Tibetan for ‘empty of other’). It is easier meditating on the luminous clarity of Buddha nature than on emptiness, because the Shentong tradition is the system that joins and connects Sutrayana with Mantrayana.

In Mantrayana, we do not proceed through the lengthy path of inferential reasoning, rather, without spending a lot of time to think a great deal about whether external phenomena are empty or not and then meditating on our understanding, we take direct perception as the path of meditation. The internal mind is the main point, so we meditate by directly looking at our mind, which is the very form of Dharmata. We look for the witness of our five sensory doors and rest in what we find, namely, emptiness and luminous clarity. As for the sixth mental consciousness that creates thoughts, we look for it by seeking answers to questions like, “Is it inside my body? Is it outside my body? Is it somewhere between the inside and outside of my body? What is its form? What is its color and shape?” We will never find our sixth consciousness and will never be able to point to it, saying, “Aha, that’s it!” Why don’t we find our mental consciousness when we look for it? Don’t we know how to look? No, that’s not the reason. It’s because thoughts are not established and have no nature of their own. Is our mind completely blank when we think we have found it? No, because our mind is capable of knowing, cognizing, and realizing things. Therefore, the sixth mental consciousness is emptiness-clarity inseparable.

Dhagpo Lhaje Gampopa taught: “This is the view: Look at your own mind.” We will not find the authentic view of the way things abide if we look anywhere else. By looking at our mind, we will find emptiness, luminous clarity, and peace, and that is the way our mind abides. That indeed is the view, and that indeed is what our mind is.

3.2. An Extensive Explanation

3.2.1. Entering Dharmata in Six Points

“Through introducing traits and a ground at all times, definitive verification as well as awareness, the recollection, immersion into its core, this six-point approach to pure being is unsurpassed.”

In the discussion of approaching and immersing into Dharmata, the first of six points is (1) ITS TRAITS. The line in the Root Text is:

“The defining traits in brief are just as they are.”

Dharmata has four traits. They are: (1) It is free from anything to be apprehended; (2) it is free from an apprehender; (3) it is free from what can be signified/expressed; and (4) it is free from that which signifies/expresses.

What is the meaning of the four traits? In many places the Buddha indicated that all phenomena are emptiness. However, just hearing that isn’t enough. If we ask, “Does that word indicate accurately and fully the nature of phenomena, the way in which phenomena abide?” No, it doesn’t. Then we might suggest and ask, “How about ‘luminous and clear or luminous clarity’? Does this point out properly, accurately, and fully the way in which phenomena abide?” No. “What about the word ‘wisdom’ (jnana in Sanskrit, ye-shes in Tibetan)? Does that word point out accurately and correctly the final nature of things?” No, it doesn’t. There isn’t a word that correctly describes Dharmata. That is why it is said that no matter which word we use, it is inexpressible. Dharmata is also inconceivable. It cannot be conceived correctly and accurately because, as it is said, it is “beyond the sphere of the minds of ordinary persons.”

In a Sutra, it is stated that the Superior Manjushri asked Lord Buddha, “Do phenomena exist or do they not exist?” The Buddha did not reply but remained silent. In commenting on this, some scholars wrote, “In saying nothing, the Buddha said a lot. He indicated that the true nature of things cannot be expressed in speech.” On other occasions, Dharmata is described as “the object of the activity or operation of each person’s self-knowledge.” The Tibetan term in this description is rang-rig, ‘self-knowing, self-existing awareness/cognizance.’ This means that we need to look at our own mind and should not look for it somewhere else. “Each person” in this quotation means that it is not an external object that we can know because somebody pointed to it, saying, “Oh, there it is. It’s over there.” Rather, every one has to look at his/her own mind to see Dharmata for himself/herself.

The second point through which to enter Dharmata is (2) ITS LOCATION. The verse is:

“The ground consists in the whole of phenomena and sacred scriptures, the whole of the Sutra collection.”

In terms of the traits, Dharmata pervades all of samsara and all of nirvana. It is in every single phenomenon of samsara and pervades nirvana entirely. It is found in all Sutras and texts of the First Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, the Middle Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, and the Final Turning of the Wheel of Dharma by the Buddha. When the Buddha turned the Wheel of Dharma the first time, he presented the teachings on The Four Noble Truths. When he turned the Wheel of Dharma a second time, he emphasized the teachings on emptiness and presented methods for realising the way in which phenomena appear and abide. When he turned the Wheel of Dharma a third time, he taught about the Buddha nature and the union of wisdom and Dharmadhatu, the Sanskrit term for ‘the expanse of being’ (chös-kyi-dbyings in Tibetan). On that occasion, he also presented methods for realising the way of abiding. So, Dharmata is the location of all Buddhist scriptures.

The next point through which to enter Dharmata is (3) DEFINITE DISCRIMINATION. The verse in the Root Text is:

“Definite discrimination applying to this is comprised of appropriate mental cultivation, based on the collections of Sutras and Mahayana scriptures, embracing the path of application in full.”

What is brought forth in this point is a discussion of the five paths (lam-lnga in Tibetan) that are covered by practitioners in their sincere endeavor to attain Buddhahood. The first is the path of accumulation. At this stage, we listen to, think about, and understand the meaning of the Buddhadharma. On the second path of joining, we meditate on the meaning of the teachings that we understood.

The fourth point is (4) KNOWLEDGE, INSIGHT, AWARENESS (rig-pa in Tibetan). The verse in the Root Text is:

“Awareness, because authentic view is attained, is the path of vision on which the suchness attained is in a fashion direct, whatever encountered.”

The meaning of rig-pa (translated here as “awareness”) is actually ‘seeing, knowing, understanding.’ It is related to the third of the five paths, which is the path of seeing. By having practiced the first two paths and by having brought what we understood into our meditation practice, we ascertain Dharmata more clearly, until we arrive at a direct perception of it. If we practice the Sutra tradition, we go by way of an apprehending consciousness, until it becomes a direct perception. If we are Mantrayana practitioners, we are introduced to the way in which all things abide, and this introduction becomes direct perception and the knowledge of what we perceive, i.e., we know and realise just how phenomena are. Then we will have gained the authentic view.

The fifth point through which to enter Dharmata is (5) RECOLLECTION. The verse is:

“The recollection applied to reality is seen. Through awareness (it) comprises the path of meditation, involving all factors inducing enlightenment, whose point it is to purge away the stains.”

Recollection is connected to the fourth path from among the five. On the fourth path of meditation, we recollect and meditate on what we realized when we practiced the third path of seeing. Rising from this direct realisation of Dharmata, we know what we saw. This is not a matter of merely remembering or thinking about what we saw, rather, we meditate and realise Dharmata again and again. In this process, we abandon more subtle obstacles to enlightenment and come closer and closer to ultimate realisation.

In dependence upon recollection, we continue practicing and arrive at fruition of our efforts, which is (6) IMMERSION. The verse in the Root Text is:

“Here, immersion into its core complete is suchness rendered free of any stain, where all appear exclusively as suchness – this in turn is transformation complete.”

“Immersion” means thorough and complete transformation. One Tibetan term in the original to describe this is that one has changed one’s home, in the sense that one lived in the midst of impure phenomena and has transformed it into a pure dwelling place. Actually, it refers to the possibility of such a transformation. The point is that impurity has been abandoned, purity has been achieved, and one sees the very nature of Dharmata. Having seen and mediated upon it, one arrives at the realisation that Dharmata is not different from oneself. In fact, it has always been like that but one has not realised it as such. By realising the non-differentiate state, it becomes manifest. This is what is meant by “immersion into its core.”

In “The Unexcelled Nature” (“Uttaratantrashastra” in Sanskrit), it is written: “Sentient beings are Buddhas, however they are obstructed by adventitious stains.” In this way, “adventitious” points to the fact that stains that prevent realisation of Buddhahood are not our nature and it is indeed possible to separate from them. When the obscuring defilements of adventitious stains have been cleared away, then it means that the place has been changed into a pure abode.

3.2.2. Transformation in Ten Points (pts. 1 – 5)

“This ten-point presentation of transformation provides an unsurpassable introduction, because it is the way to approach the essence, ingredients, and individuals. The special traits, requirements and ground, mental cultivation and application, the disadvantages and benefits.”

This verse is a brief presentation that is followed by a detailed explanation of each point. The first point in detail concerns (1) THE ESSENCE OF TRANSFORMATION. The verse is:

“Of these, the introduction to the essence includes the circumstantial stains and suchness. When these in fact do not and do appear, this is suchness, that untouched by stains.”

What is thorough and complete transformation? In the teachings that are presented in “The Unexcelled Nature,” Maitreya explained that when the Buddha nature that is within every living being is purified of adventitious stains, the gradual transformation from the state of an ordinary being to the state of a Bodhisattva and then to that of a Buddha is accomplished. Despite being in everyone, the Buddha nature is not manifest because it is concealed by the adventitious stains that are temporary conflicting defilements (such as ignorance, desire, anger, and so forth).

It is taught that the essence of a Buddha has three aspects. They are: the aspect of an ordinary being, of a Bodhisattva, and of a Buddha. How is it that there are these three aspects? As long as living beings are saturated with conflicting emotions, they are impure. When a partial purification of conflicting defilements has been accomplished, a diligent practitioner will have achieved the state of a Bodhisattva. When a complete and thorough purification has been accomplished and all conflicting defilements have been eliminated, then that is the state of a Buddha. Taking the sun as an example, when the sky is cloudy, the sun is obscured and then sunlight cannot shine through. When some clouds have dissipated, then some sunlight can come through. When the clouds have completely vanished, then the sun shines brilliantly and brightly. Like that, as long as living beings are obscured, a Buddha’s wisdom and perfect qualities do not manifest. Through the purification process that consists of the gradual removal of adventitious stains, a transformation occurs and the Buddha nature is revealed more and more clearly.

The second point of transformation concerns (2) THE INGREDIENTS. The verse is:

“The introduction to substance, ingredients: Of awareness in form of the vessel in common shared, a transformation to suchness is undergone. Of the Sutra collections’ Dharmadhatu itself, a transformation to suchness is undergone. Of awareness’ components of sentient beings not shared, a transformation to suchness is undergone. Of awareness’ components of sentient beings shared, a transformation to suchness is undergone.”

The first topic of this point is (i) phenomena that are shared with others, i.e., forms. This is associated with the discussion about the nature of what appears to be external phenomena and internal consciousnesses. We looked at this earlier. There are things that are common and shared among various sentient beings and things that they do not have in common. With respect to those that are shared, they are, for example, mountains, buildings, and whatever makes up the conventional world that serves as a container. They all bear the quality of Dharmata and abide by way of Dharmadhatu. The Sanskrit term Dharmadhatu (chös-kyi-dbyings in Tibetan) can tentatively be translated as ‘the expanse of phenomena.’ Dhatu in Sanskrit (dbyings) means “it cannot be stopped by anything, is completely pervasive and spacious.” Space is an example because it cannot be obstructed and pervades everything. In that way, dhatu (‘expanse’) is the suitability for good qualities to be generated and come into existence as well as the suitability for faults to be abandoned. Since Dharmadhatu is not an impure expanse, it is referred to as “the expanse of Dharma.”

The second topic is (ii) expressed terms and meanings, i.e., speech. Various impure names, words, letters, and so forth are used to describe meanings. They are the signifiers of that which is expressed. The nature of those impure phenomena (names, words, letters, etc.) is a lack of own existence. Regarding that which is final, we understand that Dharmata manifests as the Sutras, Shastras, and so forth. The third topic of the second point is (iii) internal phenomena, i.e., mind, particularly the eight consciousnesses. What is indicated here is that such impure phenomena can be transformed into a Buddha’s wisdom.

Although Dharmadhatu is not divided, we can make three divisions in terms of conventional phenomena. First we looked at phenomena that are shared and secondly at that which expresses, i.e., speech. Thirdly, in terms of internal phenomena, there is a great variety of knowledge that is not shared. Looking at fruition, i.e., Buddhahood, there are three sorts of divisions. They are the Dharmakaya (‘truth body’), Sambhogakaya (‘complete enjoyment body’), and Rupakaya (‘emanation body’). The Dharmakaya is related to the way all phenomena abide; the Sambhogakaya is more coarse, and the Nirmanakaya can be shown to all living beings. If we relate them with the three aspects of Dharmata, then firstly, the thorough and complete manifestation of Dharmata through transformation of location, which is shared, is related to the Dharmakaya. Secondly, by having undergone thorough and complete transformation, pure expressions of meanings manifest in the form of the Sambhogakaya. The Nirmanakaya is related to the third aspect of Dharmata and is mind’s pure and luminous clarity, awareness, knowledge (called rig-pa in Dzogchen). The transformation into an apparent state or form is the emanation body of a Buddha, the Nirmanakaya.

The third point of transformation is (3) AN INDIVIDUAL’S TRANSFORMATION. It addresses the activity of the three Kayas (‘bodies of a Buddha’). The Root Text states:

“The approach as related to individuals: The first two of these are transformations to suchness pertaining to Buddhas as well as Bodhisattvas. The last pertains also to Listeners and Self-Buddhas.”

The Dharmakaya (‘the truth body of a Buddha’) is the thoroughly and completely transformed state and therefore it only manifests in the sphere of a Buddha’s activity. The Dharmakaya is total freedom from everything that needs to be abandoned. It is a state in which all qualities prevail. Due to being free from everything that needs to be abandoned and having all good qualities, it is the fulfilment of one’s own welfare. Is that enough? No, because it is necessary to accomplish the welfare of others, too, and this is done by means of displaying a perceptible form. Therefore there is the Sambhogakaya. The Sambhogakaya (‘the enjoyment body’) manifests to and benefits Bodhisattvas who have pure karma. Is that enough? No, because it is necessary to benefit individuals who have impure karma and help release them from samsara. Therefore the Nirmanakaya (‘the emanation body’) appears in various bodies. We saw that it would not be helpful for everyone to receive the very profound definitive teachings, so the Buddha presented the indicative teachings of Hinayana for the benefit of persons with impure karma.

The fourth point of transformation deals with what is described as (4) “elevated” TRAITS OF TRANSFORMATION. The verse in the Root Text is:

“The introduction to traits especially advanced pertains to Buddhas as well as to Bodhisattvas: The distinguishing trait of totally pure domains, that which is gained through attaining the Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, as well as Nirmanakaya. The insight, instruction, and consummate mastery are attainments distinctively greater comparatively.”

Generally speaking, “transformation” means that an impure state has been changed into a pure state. The fourth point is about coming closer to the pure state and ground. It is achieved by practicing the fifth path of Mahamudra, which is called “no-more-learning.” On each ground that is reached by practicing, more subtle defilements are purified and eliminated and further degrees of enlightened qualities become manifest. These pure grounds or levels of a Bodhisattva are called Bhumis in Sanskrit, sa in Tibetan. The final and last ground is achieved at Buddhahood. So, the fourth point principally addresses the pure grounds of a Bodhisattva and the transformation of the environment into a Buddha field.

The next point is (5) REALISING WHAT IS REQUIRED. The verse is:

“The introduction to realising what is required: The distinguishing factor of previous wishing prayers, the distinguishing factor of Mahayana teaching as focal point, and the further distinguishing factor of effective application to all ten levels.”

The fifth point concerns the need and purpose of transforming one’s dwelling place and state and it leads back to one’s initial wish, smön-lam (‘aspiration prayer’) that one made, namely, to be able to accomplish one’s own welfare as well as that of others. By beginning at the first Bhumi and progressing through the following levels, one is more and more able to accomplish one’s initial aspiration prayer that one repeated, again and again. One arrives at a level at which one is able to teach the Mahayana to others and in that way to accomplish that for which one has longed and hoped.

Continued.

The photo of Thrangu Rinpoche & the dedication photo with roses & fruits from the fb, “The Most Beautiful Things in the World,” are courtesy of Teong Hin Ooi from Singapore. The teachings on “Dharma & Dharmata” were presented in Tibetan & were simultaneously translated into English by Jules Levinson. The Root Text was translated in reliance on the instructions of Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche by Jim Scott; it was published in Kathmandu, Nepal, & printed by the International Press Co. Ltd., Singapore, no. 1233, in 1992. Thrangu Rinpoche’s teachings were transcribed from the recordings that Clark Johnson from Colorado had sent by Gaby Hollmann in 1992 & in 2013 the manuscript was revised & edited again so that it is available through the Dharma Download Project of Karma Lekshey Ling Shedra, Nepal. This rendering is for personal studies only; it may not be published anywhere else & it may not be translated into another language. All rights reserved. Copyright, Munich 2013. – May virtue increase!

|